Collecting Moments

I come out the bathroom door and nearly crash into a waiter carrying a tray overflowing with plates and glasses. Like a ballerina he elegantly steps back and twists his body to avoid me, keeping the tray perfectly level as he lifts his arm to dodge the backs of the heads of the table nearby. A single glass shakes but not a drop is spilt.

I’m in the crowded Italian restaurant on Lamb’s Conduit Street, having dinner with a friend, a wonderful actor and erudite director. The restaurant is full. There’s a group of models from the nearby photography studio, happily celebrating the end of a project together, and another large group of doctors from the children’s hospital next door quietly and earnestly discussing their work. There are first dates and old friends; family dinners and business meeting. The air has that crackle that only a good restaurant in full swing can conjure.

I apologise to the waiter and compliment him on his traymanship.

“Not to worry”, he says – and then, “if your friends a reviewer tell him to write that we have been here three generations”.

“He’s not a reviewer”, I say, a little confused.

“Just the notebook made me think”, he replies.

I glance over and see W. writing in a small green notebook in short bursts.

The waiter glides into the room toward the doctors and I sit back down. I ask W. what he was writing and he explains that he’s adding a “little moment” into his list.

I’m fascinated by the notebooks of artists. If you ever have the opportunity to flip through an artist’s sketchbook or a writer’s notebook you will know how wonderful it is to see the transposition of a mind’s most raw thoughts onto a page. I remember once, for instance, flipping through an architects notes and seeing a collection of precise drawings of angles under the title, “roof possibilities”; or when I looked at a musicians notebook and saw a complicated (and for me mostly undecipherable) mix of shorthand, notation and phrases to describe the tempo of a piece – one line read, “played as if walking up slightly too steep a set of stairs”.

W. keeps a list of moments with the expressed purpose of being able to give actors suggestions of ways of doing things.

“What moment caught you eye?”, I ask.

“See that gent over there?”

“Yes.”

“See how when he puts his wineglass down, he wraps is first finger round the stem and flattens his palm over the base as if to lock it into the table.”

I look and see what he means.

“I do.”

“Now let’s say I was directing a scene, and I needed to get an actor to convey tension and nervousness. Instead of asking for that in the abstract I could ask them to hold their glass like that. Perhaps it’s the wrong gesture, but often I suggest something from my list, and it works – or at least it is a start point to arrive at something that works.”

I look at the gentleman he is referring to again. The wineglass is still locked to the table, even as the waiter pours some more into it.

“Now look at her way of holding a glass”, he continues, pointing at the woman sat with the gentleman.

She is not clamping her glass to the table. Often, she would lift it as if to drink, then say something and use it as an extension of her gestures. Sometimes she would take a sip and then set it back down with an elegant grace or she would punctuate a point by bouncing her wrist as if to make the liquid nod along in agreement with her.

“She’s light and free with it – while he has his locked to the table like it may run away”, W. says. “What does this tell us about them? He’s tense and she’s not. Perhaps it’s a first date and he’s nervous and she’s not; or perhaps she’s his boss; or maybe he’s worried about something and she’s relaxed. Suddenly we’re not talking about gestures, were telling stories”. As he says this he picks up his wine glass and bounces his wrist, mimicking the woman. The wine nods in approval.

I, like the wine, agree with W.. As a director it is useful to have a collection of moments to offer to actors. It has become a useful practice for me to consciously allow myself time in a public space to see how people behave, to watch people exist and to see what gestures I can offer to actors as a part of their physical vocabulary for an actor.

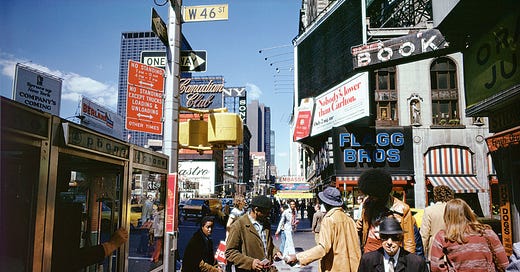

That dinner has got me thinking about these sorts of moments and about how part of the director and the actor’s job is to notice people precisely and acutely. We are like street photographers, drifting through the world with an eye that finds what moments spark curiosity. Think of that wonderful Joel Meyerowitz photograph “W. 46 St., New York City”, 1976. There are a thousand gestures and moments – of movement and expression and of character - all jostling up against one another, cohabiting and infringing on each other, dancing together. As a director being in public is like being a child in a sweetshop; it’s part of why I love it. We are all presented with countless thing that could be interesting – waiting to be stage directions or others to an actor. To collect these is a way to arm oneself to be able to talk to an actor in specifics. To say, “could you stand like this”, rather than to note, “I’d like you to stand more cooly”. It’s not that the process is prescriptive. I’m not making collage from moments I’ve cut out from the street and stuck into a play. Actors are free – in fact should – take this moments and riff on them, reject them or use them as they please.

It's a great joy to collect moments. It’s wonderful to have a job that requires me to notice and to be present in the world.

The following are taken from notebooks or borrowed from colleagues. Who knows – perhaps they will appear in some work in the future. Or maybe they’re just nice pieces of life, held in stasis.

A man checks his watch, then looks at a clock on the wall, then checks the time on his phone. He does this three times then waits a moment and checks his watch again.

In the Crown Café on the Strand the owner closes sandwich bags with an elegant flick of his wrist. He slides them along the counter with such practiced movements that they stop perfectly at the right customer.

A woman on the 214 bus phone rings. She answers, doesn’t wait even a half second and says, “fuck you, see you Tuesday”, before immediately hanging up. She gets off at Swiss Cottage.

A police officer leans on a lamppost and spins a set of keys on his finger. Two flips clockwise, one counterclockwise. He looks as if he has done this gesture an infinite number of times always the same way.

Outside a court a barrister lights a cigarette absent mindedly, seems shocked at herself and ashes it without taking a drag.

In a doctor’s waiting room a woman sneezes and says, “bless you”, to herself before giggling quietly to herself.

A guy riding a bicycle gets his trouser trapped in the chain. As he rides the hem rips. At a red light he neatly rolls it up.

A bird lands on a branch, thinks for a moment and chooses a different branch.

A student in a drama class instinctively touches the teachers arm during a conversation. She pulls her hand away quickly as if touching a hot pan. She looks at the teacher and sees that he hasn’t minded and in a facsimile of her first gesture, touches his arm again.

A barman rings the bell for last orders with a tired expression.

Note: You can see the Joel Meyerowitz I referred to in the free collection at the Tate Modern – they have a very good exhibition of his work.