Shades of Misery

Vincenzo Latronico's 'Perfection' and Mario Banushi's 'Taverna Miresia' - two different shades of misery.

By complete chance, I seem to be consuming a lot of art about misery at the moment.

I’m in Athens directing and the Epidaurus Festival of theatre, dance and music is taking place. The festival organises tours of shows to other European countries – pre-Brexit there would have been a good handful of theatres in London showing work made for the festival, now there is only one. The Coronet in Notting Hill is renowned for showing radical work and its refusal to give up its connection to European and non-English-language theatre. I recently saw Einkvan there and thought it was brilliant, so I was glad to see, a few weeks before coming to Athens, that they were showing a piece of Greek theatre made for the festival.

Taverna Miresia (Restaurant of Kindness) is a play (although somehow the word seems too narrow for it) by the Albanian born director Mario Banushi. Banushi, who lives here in Athens, has quickly become the wunderkind of Greek theatre. I regret that I haven’t seen his piece MAMI , a reflection on motherhood and how birth is ‘love in reverse’. I’m told it was incredible. Banushi is fast becoming know for his style of theatre that that manages a precarious balancing act of the absurdly grotesque and the searingly personal.

It begins in a bathroom, it feels normal except for a large neon restaurant sign sitting in the no-mans-land between audience and stage. The bathroom is dirty, the mirror stained, and an electric heater spills a sickly yellow light onto the back wall. A man played by Banushi - or maybe it is just Banushi himself, the lines between fiction and autobiography are a little blurry here – gets out of the shower. In a very English way the audience gasped at the full-frontal nudity, which English theatre culture is still very prudish about.

The man dresses, he looks in the mirror and then slowly walks out of the stage to the neon sign. It flickers. He stares at it. It flickers again as if calling to him. He lies down on top of it, almost clings to it, and falls into an uneasy sleep. There’s a blackout. The neon flickers in the dark and then dies. When the lights come back up an open grave has appeared in the floor of the bathroom and four women sit on chairs around it. Taverna Mirsesia is about a grief and misery; about losing a father and what happens when our own lives don’t make sense to us anymore.

The rest of the play comprises of surreal versions of grief: one of the sisters feeds the other, who spits each mouthful back onto her; an older woman, maybe the man’s widow, stares without blinking to the mirror; the man lies in the grave; the two sisters dance until the point of exhaustion and collapse. By a wonderful trick of stage craft people can appear seemingly magically in the shower. The bathroom becomes a laboratory of grief. No one talks to one another; there’s nothing left to say. The misery dances around the room on a strange and haunting score written by Jeph Vanger – half a requiem, half a body struggling to find breath.

Misery haunts this play. Their grief is so palpable it is rotting them from the inside. At moments it reminded me of Paula Rego’s most violent works. Like Rego’s work, Manushi’s is full of bodily fluid: there’s the spit, urine, dirty shower water splashing across the stage. For Rego and Manushi misery is like a sickness, it’s messy and stains. It leaks out of us.

I’ve talked about the art of detritus on here before – on how Tracey Emin chooses to show her own misery through a dirty bed. Manushi does the same but on stage. For him grief is exhausting but it’s also grotesque. In renaissance painting the habit is to show people crying with a single tear, to show a sterilised form of misery but Manushi knows that when we cry, when we really cry, we find ourselves covered in snot with a face reddened by burst blood vessels. Part of the bravery of Taverna Miresia is that Manushi and co. show the kind of misery that sticks to the body, that isn’t intellectual but physical. The kind that can’t find words, only wails.

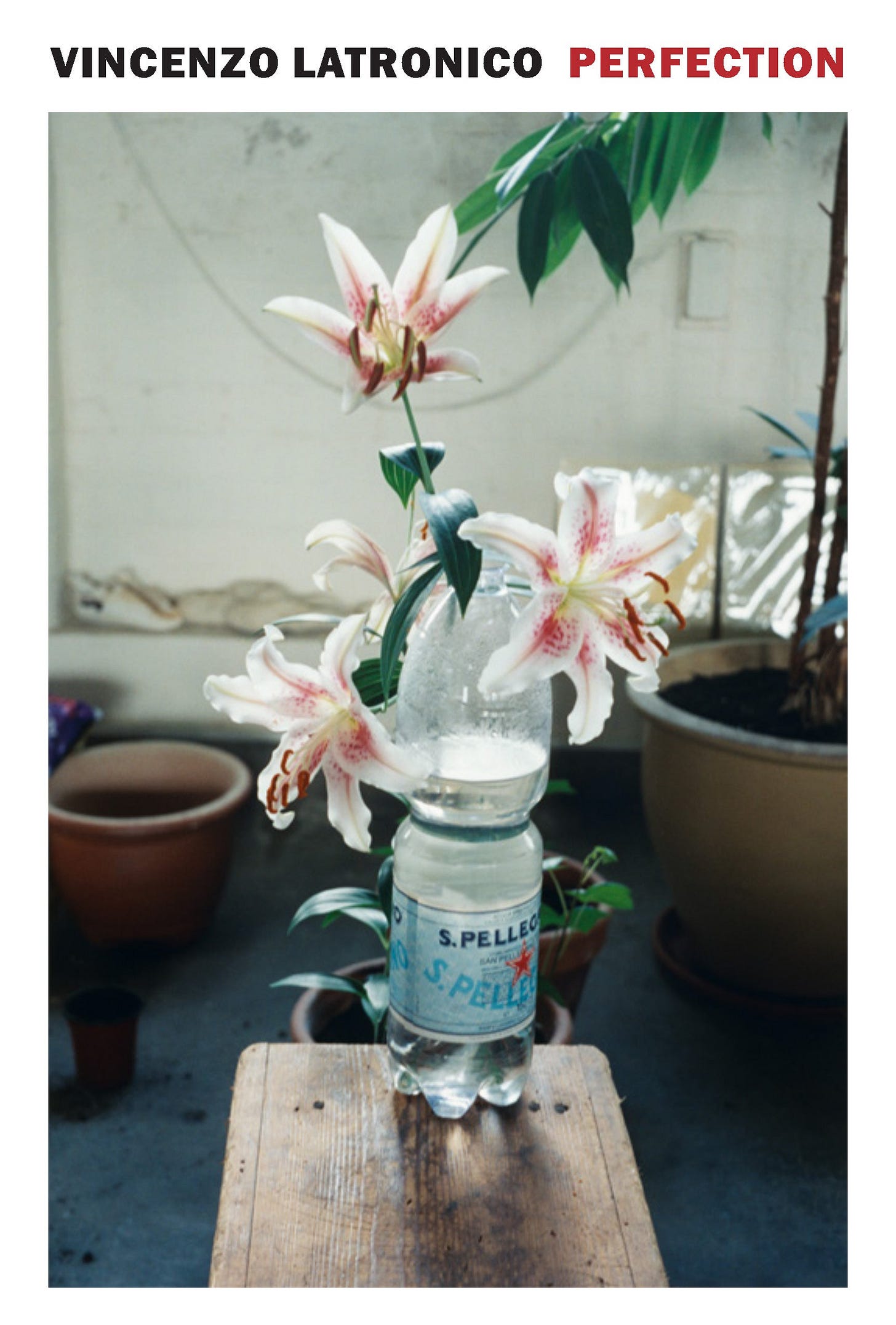

If Balushi is dealing with the physical effects of misery – from an almost early modern perspective of misery as a kind of bile – the novel Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (translated by Sophie Hughes) shows misery in the opposite way. Perfection is about a kind of sterile, clean, manicured misery.

Perfection also begins in a bathroom - stylish one, with dark blue ceramic tiles and pot plants, in an expensive apartment in Berlin’s Neukölln. The novel is a modern version of George Perec’s Things: A Story of the Sixties. In it, Anna and Tom, who like the characters in Taverna Miresia never speak, live out their lives as graphic designers in Berlin. They make endless decisions about what products to buy and how best to curate their Instagram feed but increasingly we see that beneath all the marks of consumerist successes and the personal branding, they are both bored and miserable.

The style of writing is sterile – as if describing a scientific subject in an arboretum. Anna and Tom exist in an endless cycle of self-curation, they live lives where every decision is taken with the same vapid strategy of a company trying to build a sense of brand identity. They live in Berlin but speak no German. Their ‘friends’ are an endless spiral of anglophone young professionals who arrive in the city, swirl around it’s galleries and bars and disappear just as easily. Their identity has been eroded away to a point that it only exists through the symbolic weight of their possessions. They are that perfect prey of consumerism and late-stage capitalism, people who have mistaken lifestyle for life – taste for self.

A lot of Perfection reads like those magazines about nice homes. There are long descriptions of Anna and Tom’s days spent reading the Guardian, buying coffee-table books and strolling across Tempelhof. But in between the trappings of a perfect life misery seeps through. Latronico creates two characters who have managed to cauterise the symptoms of misery but who haven’t cured it. Tom and Anna are morphinated patients, in a strange kind of overly peaceful sleep. They are making wax-works of themselves but beneath it all what we see are two empty people; unhappy with each other and exhausted by trying to curate their way to contentment. Their sex life is bad, their politics meaningless and their connection to Berlin based only on luck. They have constructed lives which look wonderful from the outside, forgetting that they themselves will never get that view.

By the end of the novel you’re left thinking one thing: perfection must be miserable.

I’m interested in these two different shades of misery; in how two very different pieces across two mediums can approach thinking about the same emotion in such different ways. Whether you watch Taverna Miresia or read Perfection, you leave with a sense that joy is to be clung to wherever it can be found because misery will come for us all at some point – either in messy slashes of grief or seeping in through the cracks of ‘perfect’ lives in expensive apartments.

If you can, see Taverna Miresia. It’s far more incredible than my writing can do justice. This blog will be less miserable next week when I write the second instalment of Notes From the Rehearsal Room.