Part of why I love theatre and dance is that they leave nothing behind. They exist only in the memory of those who have seen them. I’ve written about this before in a piece on the strange surreal feeling of seeing one’s rehearsal room empty at the end of a project.

I just finished Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie’s book The Use of Photography. Ernaux and Marie had a relationship that ran, on and off, for several months in the early 2000s. During this time Ernaux underwent treatment for breast cancer. She had surgeries and chemotherapy. The book is a series of photographs of the piles of clothes left after the two had sex. Sometimes photographed right after the act, other times the next morning. She writes:

One morning, I got up after M. had left. When I came down and saw the pieces of clothing and lingerie, the shoes, scattered over the tiles of the corridor in the sun-light, I had a sensation of sorrow and beauty. For the first time, I thought that this arrangement born of desire and accident, doomed to disappear, should be photographed.

The photographs are beautiful. Some appear like classical still-life paintings, the eroticism somehow evaporated off them through the night. Others, especially in the Fitzcarraldo edition where they are published in black and white, seem closer to abstraction – almost like Rorschach drawings.

There’s a bravery to the photographs. Ernaux underwent some of the most invasive treatments possible. Medicalised people are often told by society that sex is for others, a privilege reserved for those who are not disabled. Under patriarchy and in a time where pornography is terrifyingly available and over-consumed, we are conditioned to think of sex as being about perfection rather than joy or intimacy. But Ernaux’s (and Marie’s) photographs calmly show sex as a part of life, almost quotidian, something to neither be ashamed of nor sensationalised.

The book follows a repeated pattern: an image and accompanying texts by Ernaux then Marie. It’s interesting to see two sets of eyes cast over the same images, to see two different memories made from the same moment. The tragedy of the book is revealed as we see Ernaux and Marie drift apart. Finally exchanging their texts after they have broken up. The images get increasingly abstract as the relationship deteriorates: ‘it is as if M. has photographed an abstract canvas in a picture gallery’, Ernaux writes of the last image. ‘That is the paradox of this photo, intended to give our love more reality but which instead makes it unreal’, she continues.

Perhaps love is like theatre or dance. No amount of trying to archive it can recreate the experience of being there. All we are left with is facsimile and memory.

Or, as the musician Ian Dury puts it (another person who, albeit more openly angrily than Ernaux, rejected the idea that sex was reserved for able-bodies1): ‘moments of sadness, moments of guilt, stains on the memory, stains on the quilt’.

Ernaux starts the book by talking about the mess left on dinner tables after everyone has gone home: the dirty plates, stained napkins and half-empty glasses. For a while I made photographs of napkins after eating. Like Ernaux with clothes on her floor, I thought they looked like Abstract Expressionist painting.

The architect Sarah Wrigglesworth made this sketch, The Disorder of the Dining Table, of a dinner table before, during and after a meal while she was in the process of designing a house.

The middle of the triptych is like a long exposure photograph where time has been condensed into one moment and movements overlap themselves. Like the photographs, no people can be seen but stories can be extrapolated from their detritus. In The Use of Photography, you can see the flurry of passion interrupted by a moment of awkwardness as Marie has to untie his heavy boots just from the way the clothes have landed. Similarly, in Wigglesworth’s sketch we can see how the two people on the bottom right corner of the table must have been having a long side-conversation from the positioning of their chairs; how the person in the middle seat on the top side must have spilt their drink; how their neighbour to the right didn’t have desert from the way the spoon is still in its original place.

I had dinner with some friends last night and, as we left, I looked back at the messy table with such pleasure. It was the perfect representation of a happy night. I see a similar joy in Wrigglesworth’s dinner. I can almost hear the conversation and the music of cutlery tapping plates.

There’s something wonderful about how the mind is trained to look for human stories. Even in images of objects we seek out stories of what people must have done. As we go through our lives the detritus and mess we leave behind acts like ghostly memories, balanced on the edge of destruction, telling the stories of what we have done.

Two years ago I was cooking in my flat and realised that I had forgotten to get some of the ingredients I needed. I had already made a marinade so put that into the fridge, grabbed my keys, and ran out the door. On my way to the shops I felt the my heart was going out of rhythm (I have a condition that causes this). I fainted in the street and some passersby found me, called an ambulance and I was taken to hospital. Two days later, very sore, I came back home. Starving, I looked in the fridge. I saw my forgotten marinade from earlier and felt this complicated feeling of seeing the evidence of the timeline that would have been if I hadn’t of fallen ill. I had, until that moment, forgotten why I was walking down the street I was found on. It was difficult to see the evidence of an object from a moment that had been forgotten in the flurry of more pressing things, something sad about the evidence of the half-finished cooking preserved in that fridge.

My point is memories and stories imprint themselves on objects. Sculptures are made of what we touch on our paths through life. Dinner tables turn into maps of who spoke to who that evening. Pictures of intermingled clothes can tell us, discreetly, all about the night before. Our detritus tells our stories whether we are there with it or not.

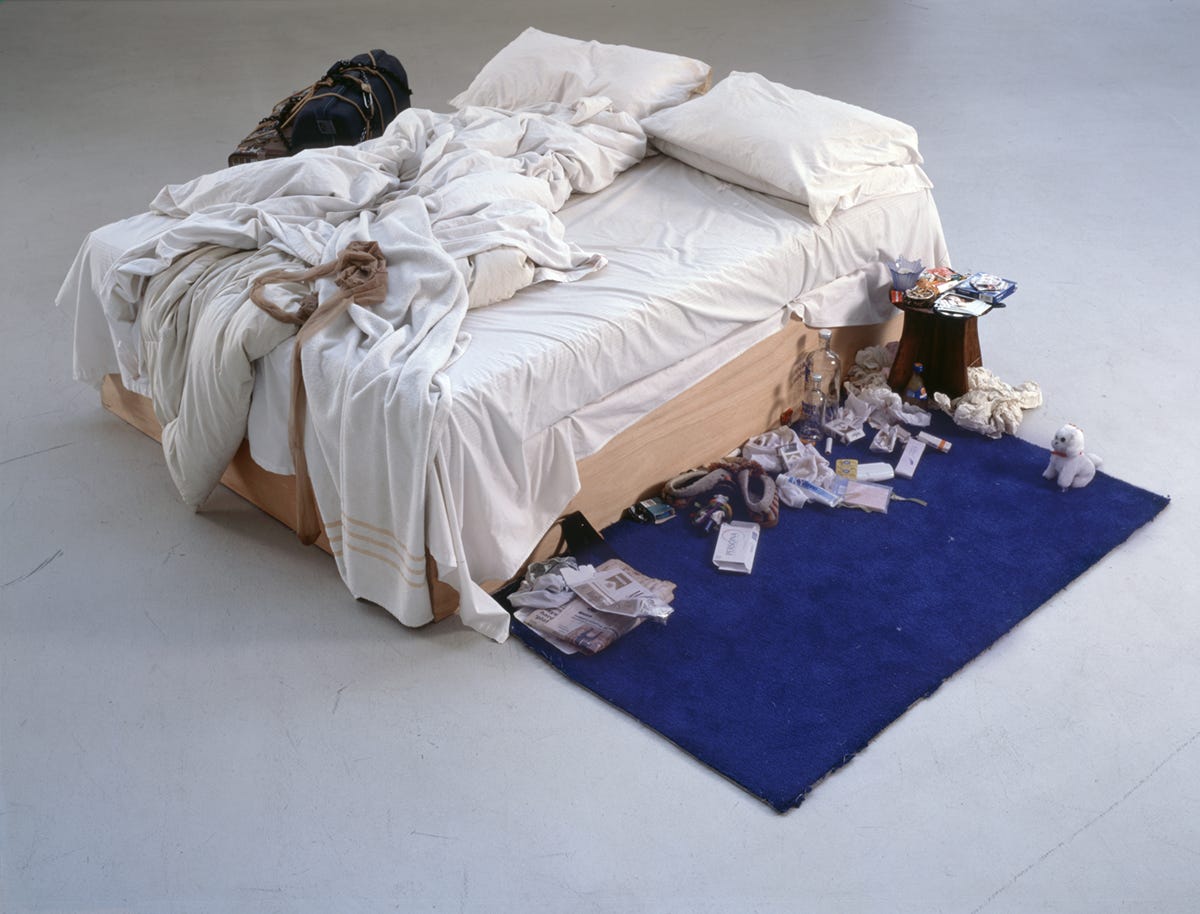

I can’t write about what we leave behind without talking about Tracey Emin’s My Bed. The bed is a replica of her bed after not leaving it during four days of severe depression. Journalists at the time churned out articles shrill with moral panic objecting to the showing of a sculpture with bodily fluids, used condoms and underwear as a part of its material list.

To me, My Bed is an incredible piece of art. One that resists the usual habit, originating from literature but now in many art forms, of glamorising depression as a motivation for making art – think of the strange ways people talk of Proust or Dostoyevsky’s depressions as some kind of heightened artistic state. Emin has managed to make a self portrait without being there. Depression consumes people. And scarily often it leaves nothing left of them. Here Emin shows that by making a work that is intimately, bravely, about her and yet which she has vanished from. Her detritus becomes her – the depression robbing her of everything except its paraphernalia.

We are what we leave behind. Art schools use this term ‘mark making’. We are all mark making all the time, leaving behind us an endless stream of objects to tell fractured versions of our stories. These marks fade as they are tidied away or replaced by new ones. It is beautiful that we can see memories, joyous and tragic, in clothes on the floor, dinner tables after the last guest has gone home and unmade beds.

I wonder why I have chosen to make theatre, an art form where nothing is left behind, where shows are ‘struck’ at the end. In a life of continual mark making there’s sanctuary in an artform that leaves no trace.

Dury had polio contracted from a public swimming pool for most his life. This quote is taken from the lyrics of Fucking Ada, a song written in the aftermath of a turbulent love affair.

Nicely thought; surprisingly illustrated; beautifully written. x