Robbed of a Metaphor

How my heart condition has distanced me from the most common and important metaphorical object.

Let me sit in a flowerpot,

The spiders won't notice.

My heart is a stopped geranium.

Sylvia Plath, Who

Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight,

For I ne’er saw true beauty till this night.

Spoken by Romeo in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Act 1 Scene 5

Two examples of the heart as a metaphorical object from two of the English language’s greatest writers. Along with light, the heart is perhaps the most used metaphor in human expression. Countless common phrases use it in their image: ‘broken heart’; ‘eat your heart out’; ‘heart in the right place’; ‘wearing your heart on your sleeve’; ‘a heavy heart’. Et cetera and et cetera. It is an image that can be used to convey great love, as we see in the Shakespeare above. Or, it can be used to convey great despair, as we see in the Plath. It seems then that is the metaphor we reach for when we need to illustrate heightened states – when we need to talk about the things that really matter like love and despair.

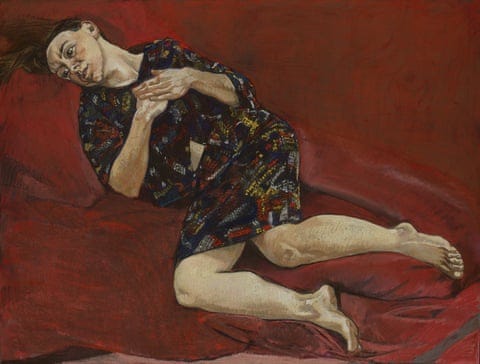

This is not just a metaphorical convention of our poets. When Paula Rego wants to show us a woman in love she positions her on a swathe of red, holding her own heart.

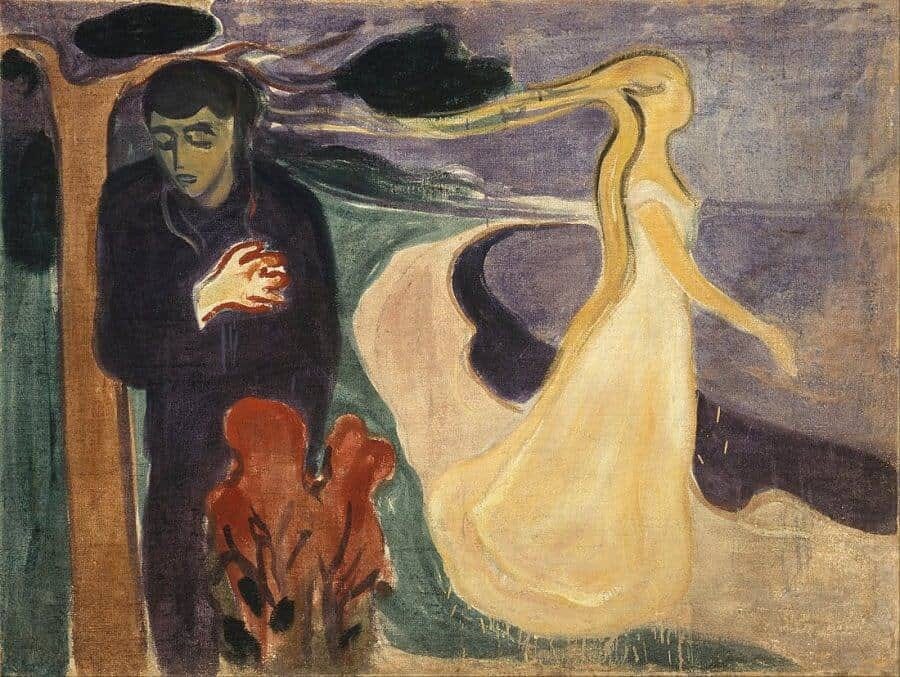

When Edvard Munch wants to show us the pain caused by separating from a loved one, where else does his figure’s hand go than to his heart?

It is the accepted poetic and metaphysical practice for the heart to be the location of the emotions that define us. It is, if we look at several thousand years of art, culture and language, the organ we choose as the stand-in for the soul. As Van Gogh writes in his letters:

The heart of man is very much like the sea, it has its storms, it has its tides and in its depths it has its pearls too.

I have a heart condition. In past posts I’ve obliquely referenced it while talking about other things. It’s a relatively new thing in my life, first appearing a few years ago. My heart has become something I am hyper-conscious of. When I have episodes of pain that awareness is obvious and understandable – what is pain if not our bodies way of directing our awareness to a problem? But when I’m feeling relatively fine, my heart is still close to the top of my mind. I notice myself looking out for defibrillators in public spaces or feeling anxious when walking over surfaces that it would hurt to collapse on. Like all disabled people, I’m aware of the large intrusions having something wrong with your body causes: the missing of social events because you’re too ill to go; the exhaustion caused by having to heal from surgeries; the harm caused to one’s career. These are all a routine part of the disabled experience.

The small things add up too. I have an implant that was surgically placed above my heart that hurts when someone hugs me a little too tightly1. That kind of small, every day, intimacy being invaded and trampled over by my condition sometimes frustrates me as much as the bigger intrusions into my ‘normal’ life. I now awkwardly hug people from the side.

Actors I work with sometimes talk about their character’s ‘heart centres’ (the term is taken from the acting teacher Rudolph Laban2). I have to consciously remind myself that they don’t mean a place of pain but one of warmth and emotional richness.

One such small thing that I have lost through my condition is that my heart is no longer the site of metaphor, the physical manifestation of my soul. Instead, it has been reduced from a poetic object to a functional one that is malfunctioning. No more when I read of, or see, the heart as a metaphor in a beautiful work of art like the ones mentioned above will I be able to engage with that purely as a poetic devise.

A few days ago I saw a colleague perform that scene from Romeo and Juliet. When the famous line ‘did my heart love till now?’ came I wasn’t just engaging with that on the level Shakespeare intended. I wasn’t completely thinking of the heart as the metaphorical centre of Romeo. I wasn’t able to see the speech for what it is, a person realising that their very being is tied up in their love for another – and one of the most beautifully written versions of that realisation ever put to page. Instead, it flipped some Pavlovian switch in me. As the actors performed, I couldn’t help but become aware of my own pulse, mentally checking in with myself that it seemed normal and regular. I began, almost subconsciously, but enough to distract me from the scene, to palpate my wrist to feel my heartbeat.

A little bizarre to say, but my heart now is something that has to really exist rather than to be an elegant shorthand for the most core of feelings and desires.

My condition has robbed me of a lot. That is the nature of disabilities. Much is being done to make spaces more accessible, but the reality is that we live in a world overwhelmingly designed by and for able-bodied folk. I expected when I was diagnosed to deal with pain and stress. To have to accept that my relationship with my body was going to change; that large amounts of my time would be spent attending appointments and recording symptoms. What I did not expect was to be robbed of a pure relationship with perhaps the most central metaphorical object in all of human expression. My heart is no longer the site of my soul, it’s been reduced to a pulsing mass of nerves, myocardium and blood. It’s a difficult thing to come to terms with. To have something in me which was always metaphorical and representative lose that alchemy and become flesh like any other organ.

Where does my soul reside now that my heart has abdicated its metaphorical duties?

A note: for those worried about their own hearts the British Heart Foundation and the American Heart Association offer comprehensive free resources and advice and are the best people to signpost you to the right places to seek help. They do unbelievably good work. If you are worried about your heart, even in a small way, seek out medical advice - better safe than sorry and all that.

Medically this implant is miraculous. It is the kind of procedure that would have been inconceivable even a half-century ago. I’m grateful to the wonderful cariology team at Hammersmith Hospital who did the surgery.

There is a whole conversation to be had about how a large amount of acting technique is deeply ableist. Lots of writing about acting assumes that performers are all abled bodied and that their bodies resting state is one without pain. Laban, for instance, is interested in the idea of grounding oneself by imagining roots coming from your feet into the ground. The idea is to make an actor feel present with, and connected to, the moment they are in. But if your bodies resting state is one that is not comfortable, a process like this is more traumatic and frustrating than meditative. There’s an equally important conversation to have about how we can foster a culture of genuine, non-performative, representation of people in the theatre.